I got asked by Dantesoft if I could share my photo processing workflow. Of course I can! It used to be quite elaborate, but these days it is quite simple.

Asset Management

The first thing to consider is where your photos will end up. After many different configurations I have ended up putting everything into Apple Photos. There are three reasons I ended up here:

- It lets me carry my entire library with me, on one or more devices

- Basic versioning, letting me store the original photo while still only seeing the edited version

- Live Photos and good video support

In addition, I also appreciate the “Moments” feature, where it creates contextual albums from metadata. It is not all roses though. The biggest downside is that the ecosystem lock-in is strong. If I want to switch to another digital asset manager I might end up with duplicates and odd formats. I trust that Apple will keep making a photo app for the foreseeable future, as it currently is a crucial part of their ecosystem package.

Update: After I wrote this, Adobe published an update to Lightroom CC with migration support from Apple Photos.

Importing

Not all images will be processed, and not all images will be processed equally. Non-RAW photos (live photos, iPhone portrait shots) will lightly be edited in the Photos app. This typically means cropping, sometimes adjusting white balance and exposure compensation.

With RAW images things are a little more elaborate. I copy them to my computer through Adobe DNG converter, making lossy DNGs without fast load data or previews. This is done to reduce file size.

A word on Lossy compression

Photo enthusiasts seem to hate lossy compression. The word “lossy” make their hairs stand up. I don’t suffer from this condition. Files from my Fujifilm X-100F will be reduced from near 50MB to less than 10MB using lossy compression. Many think of JPEG, but lossy DNGs are very different.

The key advantage is that DNGs are scene-referenced. This means the white balance is not locked, as more color information is stored. The value of changing white balance in post production cannot be overstated. The extra color data stored also increase editing latitude, compared to JPEG files.

There are other aspects to lossy DNG, like how it deals with being 8-bit and noise shaping, but that is not important. The takeaway is that if you are fine with 99% of the quality and editing latitude, lossy DNG is fine. If you lose sleep over not being able to change the demosaicing algorithm later—it is probably not for you.

So the conversion is step one.

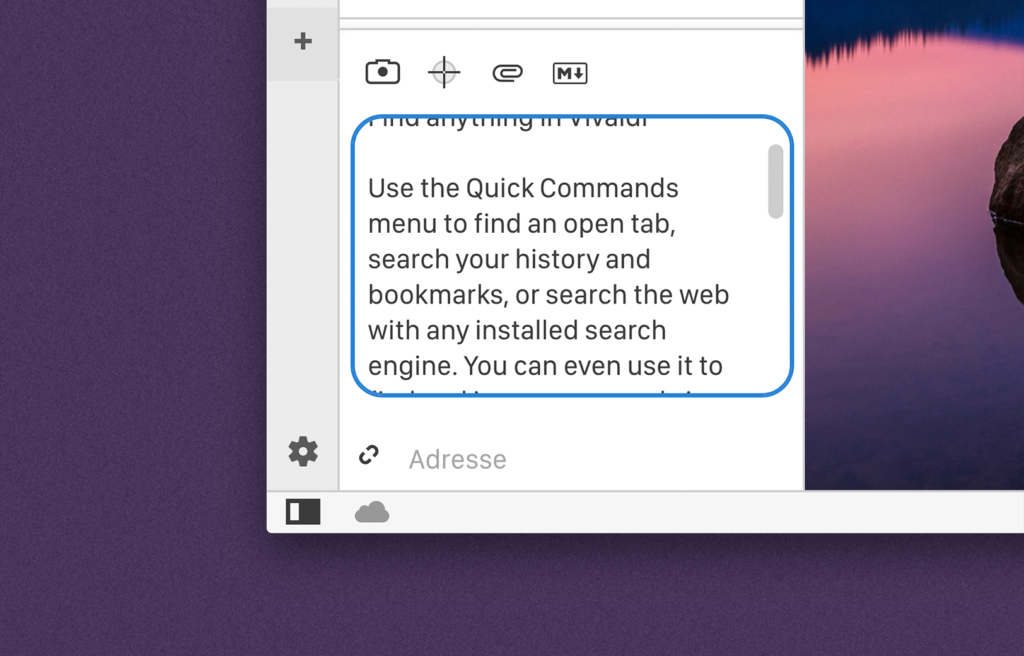

Then I import them into Apple Photos. After importing I use the External Editor for Photos extension to open the RAW in Photoshop. This triggers the Adobe Camera RAW (ACR) interface, which is where I will post-process the image.

Processing

I shoot a lot of indoor shots in “interesting” lighting, so white balance is usually a little off. My preferred way to white balance is to aim for optically correct skin tones. If possible I will use the eyedropper on a grey or white piece of cloth near the face. Should there not be anything useful near their face I will sample the white from their eye. Afterwards I adjust to taste.

Most of my shots are cropped to a 3:2 grid. Occasionally I give 1:1 or 2:3 a shot, but to me, nothing feels like a photo like 3:2. When cropping I align points of interest to the 3×3 grid.

Noise reduction and sharpening depend on gear. I will typically apply color noise reduction until there are no more bayer/x-trans filter artifacts. Luminance noise is in most cases pleasant, but sometimes it distracts from the subject and has to be toned down.

If the sky is too bright compared to the rest of the image, I might apply some masks sky (I am way too lazy to carry a polarizing filter anymore). For portraits with noisy surroundings a vignette I sometimes add a vignette, but most cameras will suffer a bit of vignette from the lens. I in many cases it is preferable to not correct that. I correct lens distortions when it is unflattering or there are obviously straight lines that suffer.

As a bonus step, I will usually apply a Fujifilm film simulation from VSCO. Once satisfied with my edits, I will export a full-resolution JPEG in sRGB and drag that into the External Editors extension.

And that’s it!